| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| All returns accepted | ReturnsNotAccepted |

| Artist | Mickey Gilley |

| Industry | Music |

| Original/Reproduction | Original |

| Genre | Country |

| Country/Region of Manufacture | United States |

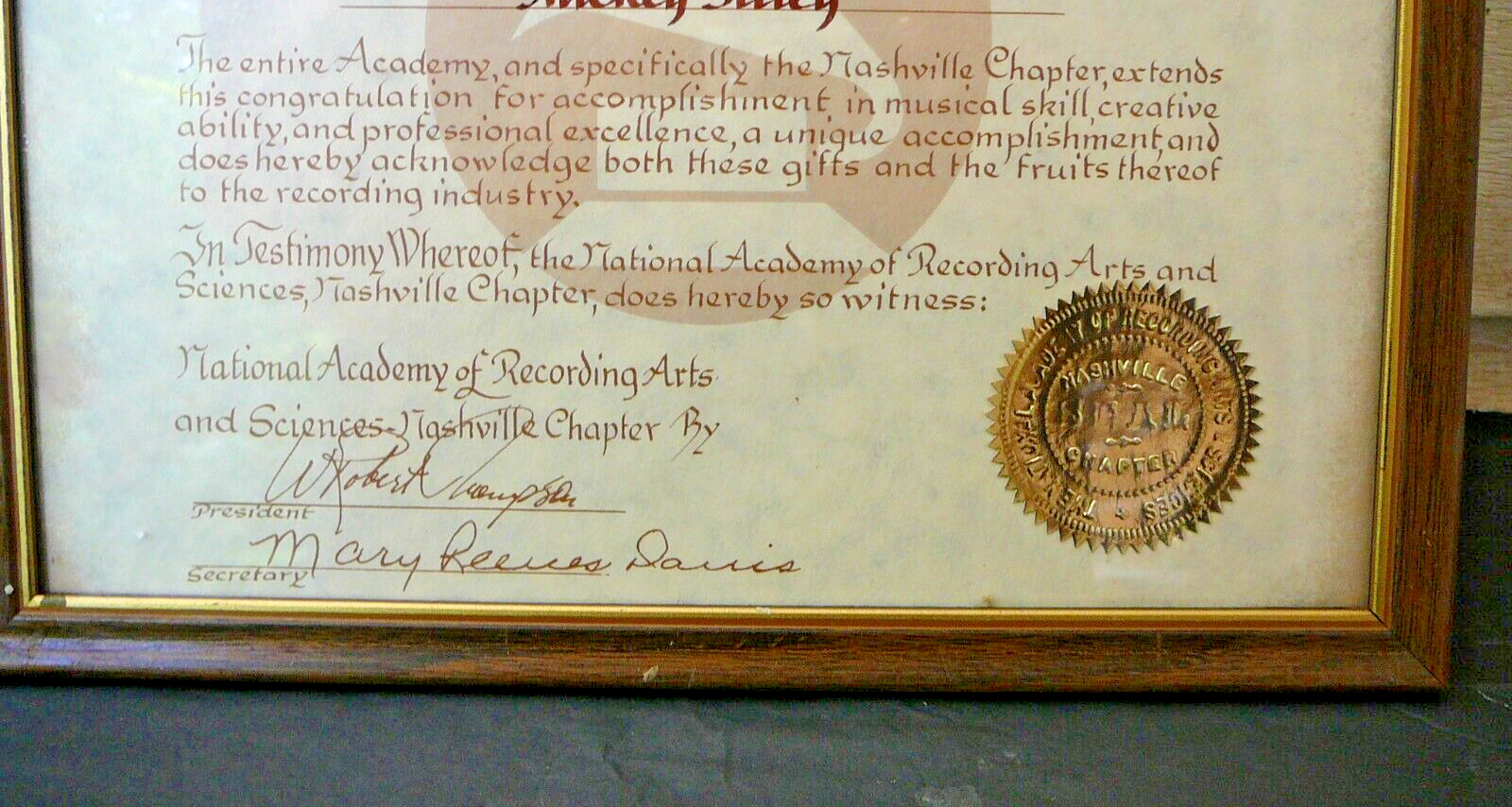

NARAS Award to Bobby Thompson. National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences. For the # 1 Hit by Mickey Gilley ” City Lights ” 1975………….. For Bobby Thompson’s Musical Contribution to this # 1 Hit song by Mickey Gilley……………………………. ” I Overlooked an Orchard ” …………………….. 1975 # 1 Hit………….. NARAS Nashville Chapter………. With Gold Nashville Seal. NARAS Record Country Music Award Mickey Gilley / Bobby Thompson 1975 Nashville This Award came from the estate of the late ” Bobby Thompson ” .Bobby Thompson (born Robert Clark Thompson; July 5, 1937 – May 18, 2005). ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Bobby Thompson Biography: Bobby Thompson (born Robert Clark Thompson; July 5, 1937 – May 18, 2005)….. was an American banjoist and guitarist. He worked as a session musician from the 1960s through 1980s. He recorded with Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, Neil Young, the Monkees, Ray Stevens, Lyn Anderson, etc among others. Thompson was born in Converse SC. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Bobby Thompson Bio On Wednesday, May 18th 2005 Bobby Thompson passed away. He was a great banjo and guitar player, one of the most requested studio musicians in Nashville in the 70s and 80s and was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1969 for his recording of Area Code 615 and CMA Award in 1985 for his performance in the Hee Haw Band. We lost our mentor, hero and best friend. Bobby Thompson: The Calm At The Eye Of The Storm Doug Green|Posted on January 27, 2022|The Archives|No Comments Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine July 1974, Volume 9, Number 1 In some far-flung corners of the world a controversy rages over who was the world’s first chromatic banjo player, but in Nashville, Bobby Thompson—one of those in the dead center of the controversy—pays little heed to it. He’s too busy as Nashville’s top studio banjo player, doing about ten recording sessions a week. Historical precedent means little to him, while his day to day life as a studio musician means a great deal. Born in Converse, South Carolina—“what you’d call a cottonmill Village”— Bobby did not come from a musically rich family, but fortunately the area was full of music and musicians, among them Buck Trent (Porter Wagoner’s electric banjoist), and the legendary guitarist Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland, who was only a couple of years ahead of him at Cowpens High School: “We both failed music!” Bob recalls with a laugh. “He’d lay out of school, and they’d catch him down by the river playing his guitar. My music teacher said I’d never amount to anything—I’d be just like that little old Garland boy. But what she didn’t know, he was doing pretty good!” Hearing “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” on the radio was a turning point for Bob, for once he’d found out what the instrument was, he immediately rushed out and bought a twenty-five dollar banjo. Although helped in his efforts to learn by an old neighbor, he “learned all my rolls backwards, and I had to re-learn them. Played that way around a year.” By the time he finished high school, banjo playing was his consuming passion: “I didn’t even stay around to get my diploma—the last day of school I cut out for Augusta,” where he found his first full-time professional job, playing with the Pritchard Brothers. Shortly thereafter, he joined an accordion player named Curly Mulligan in Greenville, South Carolina, playing both banjo and bass on a daily TV show. This is where he met Carl Story, and joined the Rambling Mountaineers, with whom he played about two years. It was while with Carl Story that he began to develop what has come to be called “chromatic” style banjo playing, for it was then that he met Flatt and Scruggs’ ex-fiddler, Benny Sims. “When I was with Carl Story he was working with Bonnie Lou and Buster in Knoxville, and lots of times we were on the same show, and he’s the one who suggested to me, I wonder what it would sound like to play a fiddle tune note for note on a banjo, and that’s when I started doing it. The first tune I worked out was ‘Arkansas Traveler.’ ” A historic moment in bluegrass music? Very possibly, but its significance seemed lost, due to a thorough lack of interest: “And when I left Carl and joined Jim and Jesse, when I’d play one of those tunes on stage, they’d just look at me like what in the world are you doing, so I just quit. Everybody had just heard Scruggs and Reno in those days, and anything else just blew on by them. I was kind of discouraged. I just played one break like that on record with Jim and Jesse, “Border Ride”, I think. But I just stuck to the Scruggs stuff. The other stuff, I just let it slide. Just stuff I’d pick in the back seat.” “I don’t think Jim and Jesse had anything against it, it was just that on stage it wasn’t accepted. You could work on one of those things six months, and they’d just sit there, but play “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and it would tear the house down.” Musical frustration wasn’t Bobby’s alone in that incredibly talented band. He particularly remembers those days in terms of Jesse’s unique mandolin style: “Oh, I think he was frustrated too.” The first time I worked with him, no matter what time we got to bed he was up at seven o’clock in the morning, and he’d always write a tune, every morning. He’d get me, Vassar Clements, and we’d just sit around and work it up. Next day was a different tune…and now, I’d give anything for just part of those tunes we did! We never got the rest of the band to learn any of them—the next day, there’d be another one. Just having fun.” Those days of fun and frustration soon came to an end, however, when Bobby was drafted. As opposed to some musicians who play a good bit while in the Army, often for good pay in local clubs, Bobby played practically not at all. “Only playing I did was this one Sargent had this one tune, “San Antonio Rose”, and when he got drunk, and I’d play that tune, I got out of all details for the next week!” After his release, he went back for another stint with Curly Mulligan for about six months. “Then I went back to Spartanburg and just quit playing for four years. I just worked in a machine shop.” It was at this time that he first heard and heard about Bill Keith, whose name has since been immortalized by chromatic banjo players who call their style “Keith Style”. “I can’t remember the first time I heard Bill play… may be it was on the Opry. The first tune I heard him play was “Sailor’s Hornpipe”, and I thought it was great!” Did it bother him that Keith was getting applause where he got blank stares? That Keith was getting credit for a style Bobby had been playing in 1958? If so, he doesn’t show it: “Bill went further with it than I had, ’cause I’d kind of stalled out and pretty much forgotten about it. I know there was two years there where I didn’t much touch it.” Pressed further, he says “I know everybody always asks me this, and I really don’t have no good answer. I don’t know if he got anything from me, or if he just run up on it same as I did.” You don’t get the feeling so much that he’s being evasive, but that he just doesn’t care. It’s just not that important to him. After a couple of years in Spartanburg, he finally took his banjo out of the case, “and the more I played, the more I wanted to. It was just like learning all over.” Jim and Jesse had been calling from time to time throughout those years, and finally, fed up with the machine shop, he and his new wife moved to Gallatin, Tennessee, and he once again became one of the Virginia Boys. But, after a year and a half, he “got tired of the road again, and we moved into Nashville and went to work in a machine shop again, six months—had to put up with that again.” It was at this time he began picking up record sessions—“maybe two a month”—largely, he feels, because up until that time, there had been no banjo player who was around town just for that purpose. He soon quit the machine shop “and starved for about six months”, getting all the session work he could, which wasn’t unfortunately all that much. A friend, studio bassist Bobby Dyson, said he could get Bob a lot more studio work if he would learn acoustic rhythm guitar, and though he claims he’d never held a straight pick before, he was soon quite busy—a valuable man in the studio because every recording session uses a rhythm guitar, and a man who can over-track on a lead instrument in the same session is a definite economic boon to the record companies. Instead of paying full session pay (about $96 currently) to a banjo player to record on only one song of three or four they plan to record, they can hire Bobby to play rhythm on all the songs, and pay him a relatively small “doubling” fee for his banjo work on the one tune where it is wanted. These humble and austere beginnings have led to Bob’s current position as one of the most successful and respected studio musicians in Nashville. Although he admits that he didn’t like studio work on guitar much at first—it was either that or back to the machine shop—he now enjoys it, not only because of the stimulating creative atmosphere, but because of the constant input of different musical styles: “I like to do different things. I was kind of rooted to one style when I started, but I like all the different things now” Although as much as 70 percent of his recording sessions are on rhythm guitar (with frequent doubling), working with both instruments has, overall, been helpful: “I think both instruments help each other in a way—they hurt each other in a way—but I’m playing rhythm on different kinds of music, and can take some of those things and adapt them over to the banjo. And I can take some banjo things and adapt them over to the guitar, so it kind of helps out.” How has it hurt? “Well, like this week I’ve sat with a straight pick all week, and I put on fingerpicks, and for about two hours my fingers won’t hardly move!” So today Bobby stands at the peak (at least in his eyes) of his profession, aware but unconcerned on controversy over events of fifteen years ago. He feels as creative now as he did then, only this time, his talents are both greatly appreciated and handsomely rewarded.

There are no reviews yet.